What is nutritious movement?

You know how they say sitting is worse than smoking?

In lockdown, I’ve spent the past months mostly sitting down. Sure, I sit in different ways and places: on the floor, in hard chairs, on the soft couch. I move around, but I don’t go out and about like I used to. I know my movement has lost… variety.

Now my body is saying, this is not good. It has its own language.

An arresting pain shoots down my right hip and leg. My osteopath has instructed me to stop sitting. To go for lots of long, long walks.

After so many months living through this pandemic, you might also be hearing new messages from your body. It makes sense. Along with everything else, our way of living in the world — and I mean, moving through it, physically — has likely changed, too.

So I installed a standing desk in my office. (One with a hand crank and not a button: the more inconvenient movement the desk requires from me to use it, the better!) I also purchased a pilates ball — a big white pearl that is pleasantly bouncy. I’m happy to say that using both, alternating with floor sprawls and long walks, has helped ease the pain.

And I’m sharing an older post with you today, because it’s even more relevant today than when I first shared it.

I read Katy Bowman’s book, Move Your DNA, on my osteopath’s recommendation. (Katy Bowman has since published another excellent title, Movement Matters — a collection of essays on the nature of movement that are a joy to read, and more relatable for people who don’t know the details about anatomy and biomechanics.)

Learning about what Katy calls “nutritious movement” inspired me. I got it: sitting for hours every day is no good. But there’s more to it than that.

A variety of movement is important to a healthy body, just like food.

As I read each chapter, I only wanted to move more and more, and sit at my desk less and less.

Okay, but… if I’m supposed to move and crouch and walk all the time, like my hunter-gatherer ancestors (instinctually, this feels healthier and better), how can I also write?

How does Katy Bowman write her books? I mean, she’s an author, too. She has a website. She’s got to have a laptop. And a chair, right?

I asked Katy if she would give us advice. Show writers how to write books without ignoring our bodies. She said yes.

Keep reading to learn how to make your writing life more dynamic.

A Writer Who Moves, A Mover Who Writes

I write a lot, mostly about movement — how to move, and more specifically, the biological need for movement — nutritious movement. Nutritious Movement describes not just the movements we need, but also the frequency at which we need them — not for flat abs and a well-toned butt, but for our basic biological systems to function well.

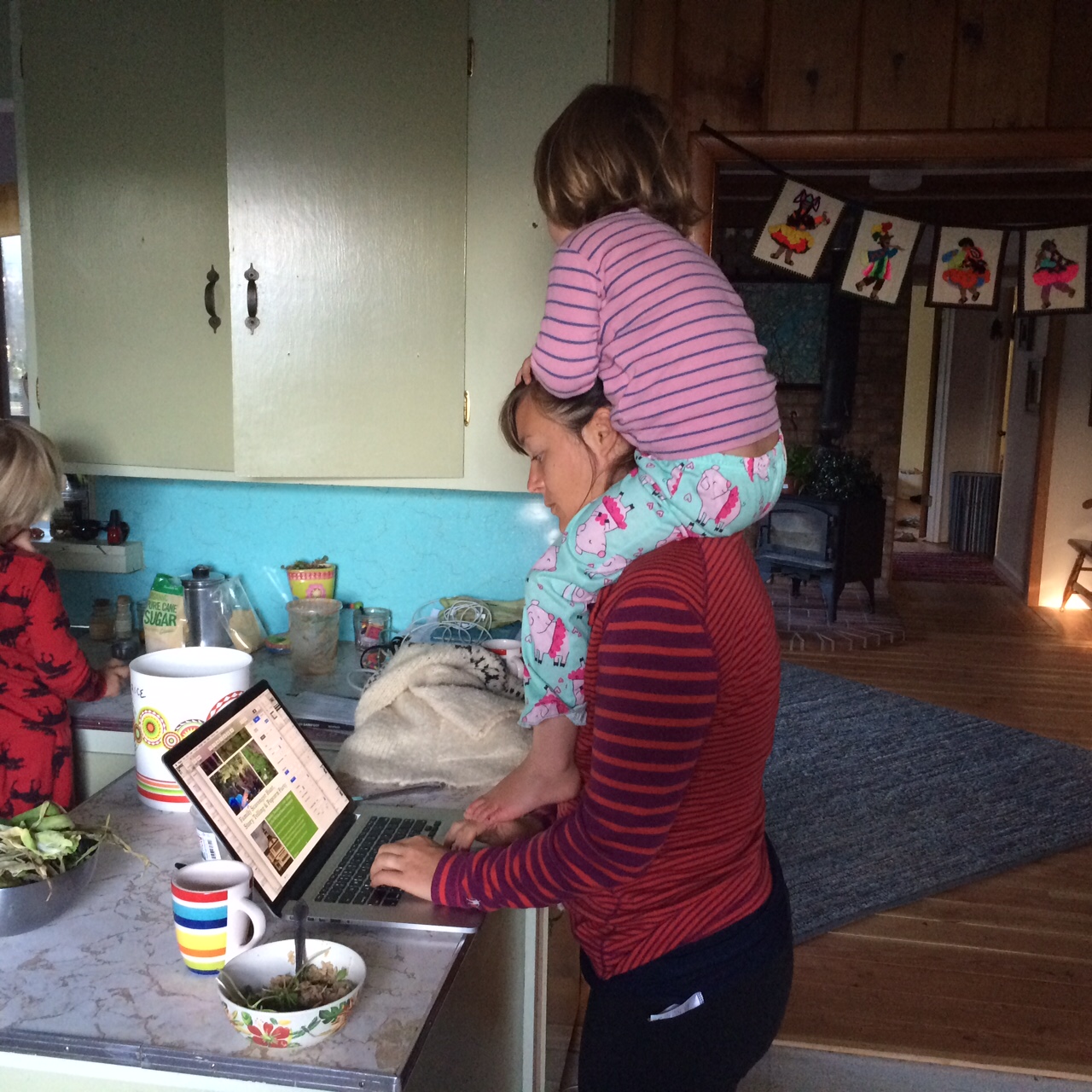

(These books have all been published since 2011. I also write for my website, have a podcast, and an entire business that is not being a writer. I have two kids. I credit my ability to pull all this off entirely to my commitment to a movement-based lifestyle.)

I’ve written nine books and hundreds of blog posts about movement since 2011. I choked on my coffee when my editor pulled five years of writings from my professional Facebook page and found they amounted to over a hundred thousand words.

One hundred thousand words, on Facebook.

While I would never claim to be a good writer, I am certainly a very productive writer, and a successful one in terms of readers reached; my work has motivated hundreds of thousands of people to move. I believe this is because, whether good or not, my writing is authentic. I’m a so-called expert in movement science — our need for movement — and I believe my message is heard (and my posts are read, and my books are sold) because I haven’t decreased my own frequency of movement in order to write about the human need for it.

Culturally, we still hold the belief  that the relationship between time and productivity is direct. As if writing consists solely of the output of words, your typing speed being the indicator of how long it would take to write a thousand-word word article (ten minutes) or a novel (one week). But of course, time spent coming up with ideas and themes, and organizing and reorganizing these threads in our minds, is also “writing.” The trouble is, we’ve come to see sitting at a desk as an integral part of the writing process. We imagine the mulling, the idea-forming, the organizing, the process — the creativity — can occur only when the butt-chair circuit is closed. I (and researchers) have found the opposite to be true: movement can be a conduit for creativity.

that the relationship between time and productivity is direct. As if writing consists solely of the output of words, your typing speed being the indicator of how long it would take to write a thousand-word word article (ten minutes) or a novel (one week). But of course, time spent coming up with ideas and themes, and organizing and reorganizing these threads in our minds, is also “writing.” The trouble is, we’ve come to see sitting at a desk as an integral part of the writing process. We imagine the mulling, the idea-forming, the organizing, the process — the creativity — can occur only when the butt-chair circuit is closed. I (and researchers) have found the opposite to be true: movement can be a conduit for creativity.

The chair, so intertwined with our humanness these days, has become, in our minds, tangled with our writing process. And so we sit and sit and sit, diligently attending to our process, when what we think of as our process is probably less tied to sitting, and more related to the passage of time. Sometimes you just have to wait for the next idea. While the waiting seems to be, at least for me, part of the writing process, sitting still while waiting doesn’t have to be.

What if you could give your body the movement it desperately needs, and also work diligently? What if you started moving while you were waiting for inspiration, for the next idea, for the next paragraph?

I’ve found that I’m not just passing time creatively when I’m moving,  but that movement actively helps my work in two ways. Like you, I have many other obligations beyond writing. I have work and household errands, and a family to tend to. And so I’ve learned to accomplish some of my mindless tasks with movement — a walk to the post office to mail out review copies of my books, for example — during my work/writing time. The break from my screen coupled with movement-based tasks gives me both time to format great ideas and more time to write them down once they’re flowing.

but that movement actively helps my work in two ways. Like you, I have many other obligations beyond writing. I have work and household errands, and a family to tend to. And so I’ve learned to accomplish some of my mindless tasks with movement — a walk to the post office to mail out review copies of my books, for example — during my work/writing time. The break from my screen coupled with movement-based tasks gives me both time to format great ideas and more time to write them down once they’re flowing.

But not only can you do much of the “background” work of writing while doing big movements away from the desk, you can also move while you write. I write every day, often for hours, and I know I’ll suffer some biological consequence if I keep still during my writing time. So I move in subtle ways that don’t require me to move away from my keyboard.

Here's what an hour of me writing dynamically looks like (sped up because who has an hour to watch someone else work?)

This kind of movement might be confusing at first, especially when our only understanding of movement is exercise. In fact, most of my books challenge that very idea — that exercise is the only way that we, a sedentary culture, can nourish our bodies. The cool thing about cells is that every motion counts as a movement to them — even changing up your body’s geometry. The physical act of writing requires you to stay in front of your computer (or your paper and pen, or crayon and napkin), but it does not require that you stop moving, stop changing your position, or stop nourishing your body.

The easiest way to start is to swap your sitting desk for a standing one and start taking a ten-minute walk every hour. But these changes aren’t really enough to get writers out of the “sedentary job” category. Changes in body geometry need to be frequent, and the shape that you are assuming while you write needs to vary more than the two positions of sitting and standing.

While I’m engaged in actually writing (vs. mulling, planning, interviewing, meeting with other people, wondering, or procrastinating, all of which I do while walking or climbing trees with my kids or otherwise being active), I cycle between a standing and floor-sitting desk. My standing work station is littered with massage balls, textured mats, and devices specifically designed to keep your body active while standing there.

My floor-sitting desk allows me various geometrical  options: sitting cross-legged, folded-legged, with legs spread into a V, and in many more ways. I’ll haul my laptop around the house and crouch near a window, lie on my stomach, and sometimes just forward bend while working. I take frequent eye breaks to look into the distance. I squat at my desk for a while, then stand at the counter.

options: sitting cross-legged, folded-legged, with legs spread into a V, and in many more ways. I’ll haul my laptop around the house and crouch near a window, lie on my stomach, and sometimes just forward bend while working. I take frequent eye breaks to look into the distance. I squat at my desk for a while, then stand at the counter.

I kneel outside for a bit, then sit down. Then I take a ten-minute walk, or sometimes even a two-minute one, which comes so much easier because I’m not forcing stiff and weakened legs out of a chair once an hour — I’ve been moving the entire time.

If you want to be a mover who writes,  or a writer who moves, or even just a mover, you must become more dynamic, and live a more dynamic life.

or a writer who moves, or even just a mover, you must become more dynamic, and live a more dynamic life.

Break your body free from that one particular configuration, that exclusive shape of your body you’ve come to associate with “writing.”

Limber and strengthen your muscles and joints so they can be used in many different ways — all while you’re writing.

Organize your day (and mind) so that lulls in actual writing — the space you hold for thinking and planning — are filled with movement.

Learn to “stack your life” so that your movement is not for movement’s sake, but accomplishes other tasks essential to your life (grocery shopping, going to the post office, visiting friends, getting coffee), leaving you with more time to write…and move.

Bestselling author, speaker, and a leader in the Movement movement, biomechanist Katy Bowman is changing the way we move and think about our need for movement. Her nine books, including the groundbreaking Move Your DNA and Movement Matters, have been translated into more than a dozen languages worldwide. Bowman teaches movement globally and speaks about sedentarism and movement ecology to academic and scientific audiences. Her work has been featured in diverse media such as the Today Show, CBC Radio One, the Seattle Times, and Good Housekeeping.

One of Maria Shriver’s “Architects of Change” and America Walks “Woman of the Walking Movement,” she has worked with companies like Patagonia, Nike, and Google as well as a wide range of non-profits and other communities, sharing her “move more, move more body parts, move more for what you need” message. Her movement education company, Nutritious Movement, is based in Washington State, where she lives with her family. Find corrective movement programs at nutritiousmovement.com.

Photo credit: Ahmad Odeh on Unsplash.

0 comments

Leave a comment